What is Bronchiectasis & Why Nutrition Matters

Bronchiectasis is a chronic lung condition where airways are permanently dilated, leading to frequent infections, inflammation, mucus build-up, and damage. Because of this:

- The work of breathing is increased. Lungs need more energy, and respiratory muscles need to function well.

- Chronic infection/inflammation can increase metabolic demands (you burn more just to fight off infection / maintain immune responses).

- Exacerbations (flare-ups) often cause additional stress, appetite loss, more energy consumption, more mucus production.

- Malnutrition (loss of weight, especially muscle) weakens immune function, delays recovery, reduces lung function, increases morbidity and hospitalisations.

On the other hand, being overweight or obese isn’t benign either: excess fat can restrict lung expansion, increase work of breathing, can worsen inflammation, and may contribute to comorbidities (e.g. cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance) that add risk.

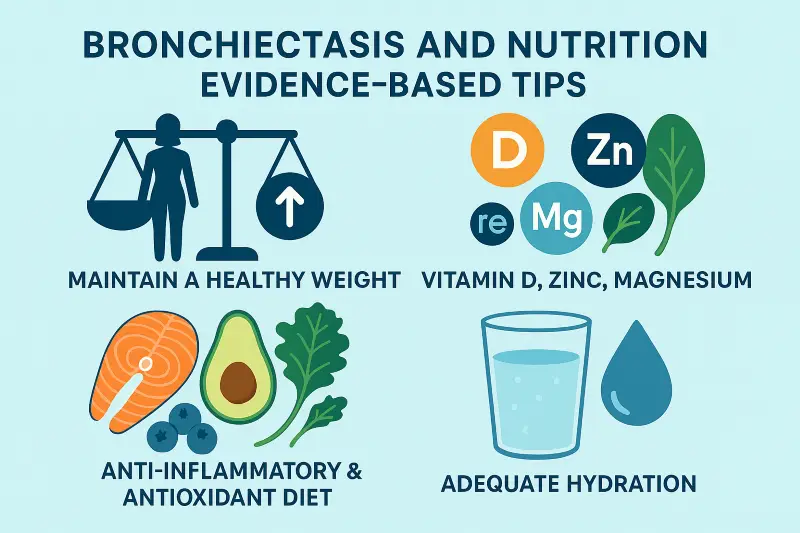

So the goal is maintaining a healthy weight with sufficient muscle mass, adequate nutrient intake, and managing micronutrients that are often deficient in patients with bronchiectasis.

Evidence for Key Dietary / Micronutrient Factors in Bronchiectasis

Here are what the studies show about specific nutrients & dietary patterns in bronchiectasis.

| Nutrient / Factor | What the Evidence Says | Why It’s Important | Sources & Practical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy weight / preventing malnutrition | Many bronchiectasis patients are underweight or lose weight unintentionally. Lower body weight / BMI correlates with worse lung function, more frequent exacerbations, poorer quality of life. | Adequate energy intake needed to support basal metabolism + extra demands (e.g. fighting infections, breathing, mucus production); muscle mass is critical (respiratory muscles, immune cells) | Work with a dietitian; track weight (and where possible muscle mass or body composition); use energy‐dense foods, oral nutrition supplements when needed; small, frequent meals; fortification of meals; during exacerbations, early nutritional intervention. |

| Vitamin D | Low vitamin D status is common in bronchiectasis; studies show vitamin D deficiency is associated with more frequent pulmonary exacerbations, chronic infections (especially with Pseudomonas), and poorer lung function. Supplementation may help, though studies are still limited. | Vitamin D supports immune function (reducing infection risk), reduces inflammation, helps maintain bone health (important since corticosteroids or inactivity can impair bone density). Poor bone density has been observed in bronchiectasis. | Check serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D; if low, supplementation under medical/dietetic supervision; ensure adequate dietary intake (oily fish, fortified dairy or alternatives) and safe sun exposure; monitor calcium too. |

| Zinc | Some evidence (from studies in respiratory infections more broadly) indicate that zinc deficiency impairs immune defence, increases infection severity. In bronchiectasis, although fewer direct trials, zinc is highlighted in reviews of micronutrient roles. | Zinc is involved in immune cell function, antioxidant properties, helps maintain barrier function, helps repair tissues. Infection burden in bronchiectasis is high, so deficiency can worsen outcomes. | Include zinc-rich foods: meat, poultry, seafood (e.g. shellfish), legumes, nuts; in cases of confirmed deficiency consider supplementation under supervision. Be cautious: balance is needed—too much can interfere with absorption of other minerals. |

| Magnesium | Less direct bronchiectasis-specific data, but in related lung diseases (COPD, asthma), low magnesium is associated with worse lung function, more symptoms. Reviews of micronutrients point to magnesium among important ones. | Magnesium aids muscle function (including respiratory muscles), helps regulate airway tone (bronchodilation), plays roles in inflammation regulation, oxidative stress. Also important in bone health. | Ensure dietary sources: green leafy vegetables, nuts, seeds, whole grains; consider supplementation if dietary intake low and under medical/dietetic advice. Monitor any interactions with other medications. |

| Other Micronutrients & Dietary Patterns | • Antioxidants (vitamins A, C, E, selenium) seem beneficial in reducing oxidative stress, which is elevated in bronchiectasis. • Adequate calcium for bone health. • Omega-3 fatty acids may help via anti-inflammatory effects. • Fibre, fruits, vegetables are protective in lung conditions generally; may help reduce infection risk and inflammation. • Adequate fluid intake to keep secretions less viscous. | These nutrients & patterns help with: reducing inflammation; protecting lung tissue; supporting immune response; preserving bone and muscle; helping with mucus clearance. | Aim for a varied diet including fruit & veg (various colours), whole grains, oily fish, legumes, dairy or fortified alternatives; avoid overly processed foods, limit excessive saturated fats; drink enough fluids; perhaps include probiotic foods to support gut-lung immune axis. |

Practical Tips for Patients: Personalising your Bronchiectasis Diet

Here are evidence-based, practical dietary strategies for people with bronchiectasis.

- Work with a dietitian – Tailored advice is best to personalise the diet to your individual needs: assess current dietary intake, weight history, lung function, blood tests (for vitamin levels etc.), comorbidities, medication effects. Use dietitian support to monitor progress.

- Maintain or reach and sustain a healthy weight – If underweight or losing muscle: increase energy density of meals (add healthy fats, protein), eat small frequent meals/snacks. Use oral nutritional supplements if needed. If overweight: aim for gradual weight loss (0.5–1 kg/week) preserving muscle mass via adequate protein + exercise (if possible). Avoid crash dieting. Monitor weight regularly; also consider body composition (muscle vs fat) when possible.

- Protein – Increased protein is key for maintaining/repairing lung tissue, for immune function, for preserving muscle. Include sources like meat, fish, dairy, legumes, nuts. Aim for protein at each meal/snack if appetite allows.

- Optimise micronutrients – Vitamin D: ensure sufficient levels through sun exposure, diet, supplements if deficient. Calcium: for bone health, especially if steroid use or inactivity. Zinc, magnesium, selenium, vitamins A/C/E: get through diet; supplement only if lab tests show deficiency. Test for deficiencies when clinically indicated.

- Anti-inflammatory & antioxidant diet – Foods rich in antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds (berries, leafy greens, colourful fruit and vegetables, oily fish with omega-3s) may help modulate inflammation in the lungs and may reduce exacerbation frequency.

- Adequate hydration – Keeping well hydrated makes mucus less thick, easier to clear. Dehydration tends to worsen sputum viscosity. Aim for the equivalent of ~8 cups of fluid per day, adjust for climate, activity, medication, and individual factors.

- Manage exacerbations – During flare-ups: appetite likely reduced; energy needs higher; focus on easy-to-eat, energy-dense, protein-rich foods; possibly use supplements; avoid further weight loss.

- Lifestyle adjuncts – Physical activity (as tolerated) helps maintain muscle mass, improve lung function. Smoking cessation is critical. Good sleep, controlling comorbidities (e.g. diabetes) supports nutritional status.

- Bone health – Bronchiectasis is associated with reduced bone density. Vitamin D + calcium intake are central; weight-bearing exercise, avoiding long-term corticosteroid side effects, and monitoring bone density may be required.

What the Evidence Doesn’t Show (or Is Uncertain)

- There are relatively few large, randomised controlled trials specific to bronchiectasis for many micronutrients (e.g. zinc, magnesium). Much evidence is indirect, or from related lung disease (COPD, asthma).

- Optimal doses of supplementation (beyond treating deficiency) aren’t well established. Oversupplementation can have risks.

- Long-term outcome data (e.g. on lung function decline, exacerbation rate, mortality) from dietary interventions in bronchiectasis is limited.

- Specific diets (e.g. low dairy, specific anti-mucus diets) have weak or mixed evidence.

Sample “Bronchiectasis Diet” Guidelines

Here’s a sample template of what a bronchiectasis diet might look like (modifiable per individual):

| Meal | What to Include |

|---|---|

| Breakfast | Oat‐based porridge (with milk or fortified plant milk), topped with nuts/seeds, berries. Add a spoon of yoghurt (for protein + probiotics). |

| Mid-morning snack | Smoothie with protein (milk/yoghurt + protein powder or nut butter), fruit, green leaf, maybe a small oats addition. |

| Lunch | Lean protein (chicken/fish/legume), whole grains (brown rice/quinoa/wholemeal bread), vegetables (leafy & colourful), healthy fat (olive oil, avocado). |

| Afternoon snack | Handful of nuts + piece of fruit; or cheese + multigrain crackers + veg sticks. |

| Dinner | Oily fish at least twice a week; or other protein plus vegetables, healthy carbs. |

| Evening snack / Before bed (Avoid if history of GERD) | Protein‐rich snack (milk, yoghurt, cheese, nut butter), or nourishing drink if appetite small. |

Ensure fluids are spaced through the day: water, herbal teas, diluted juice; avoid overly caffeinated or alcoholic drinks which may dehydrate.

GET IN TOUCH

Schedule a Visit with Dr Ricardo Jose

Disclaimer: The information provided in this article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment